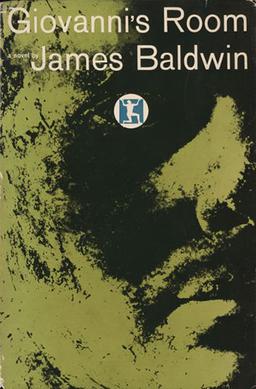

Giovanni's Room Introduction James Baldwin tended to write controversial novels, and Giovanni's Room was definitely controversial when it was published in 1956. Baldwin was born in Harlem, NY in 1924. In his teens, he worked as a Pentecostal preacher, under the influence of his father. Giovanni's Room is a 1956 novel by James Baldwin. The book focuses on the events in the life of an American man living in Paris and his feelings and frustrations with his relationships with other men in his life, particularly an Italian bartender named Giovanni whom he meets at a Parisian gay bar. In the novel Giovanni's Room, the setting, or where the story takes place, is Paris, France in the 1950s. The story follows David, a young man from Brooklyn who decides to leave everything. Giovanni’s Room is a novel written by James Baldwin in 1956. It is well known for bringing complex representations to the forefront of public conversation. These include both homosexuality and bisexuality, and were introduced to an audience that was primarily empathetic and artistic.

| Author | James Baldwin |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Gay novel |

| Publisher | Dial Press, N.Y. |

Publication date | 1956 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Pages | 159 |

| OCLC | 44800071 |

Giovanni's Room is a 1956 novel by James Baldwin.[1] The book focuses on the events in the life of an American man living in Paris and his feelings and frustrations with his relationships with other men in his life, particularly an Italian bartender named Giovanni whom he meets at a Parisian gay bar.

Giovanni's Room is noteworthy for bringing complex representations of homosexuality and bisexuality to a reading public with empathy and artistry, thereby fostering a broader public discourse of issues regarding same-sex desire.[2]

Plot[edit]

David, a young American man whose girlfriend has gone off to Spain to contemplate marriage, is left alone in Paris and begins an affair with an Italian man, Giovanni. The entire story is narrated by David during 'the night which is leading me to the most terrible morning of my life,' when Giovanni will be executed. Baldwin tackles social isolation, gender and sexual identity crisis, as well as conflicts of masculinity within this story of a young bisexual man navigating the public sphere in a society that rejects a core aspect of his sexuality.

Part one[edit]

David, in the South of France, is about to board a train back to Paris. His girlfriend Hella, to whom he had proposed before she went to Spain, has returned to the United States. As for Giovanni, he is about to be guillotined.

David remembers his first experience with a boy, Joey, who lived in Brooklyn. The two bonded and eventually had a sexual encounter during a sleepover. The two boys began kissing and making love. The next day, David left, and a little later he took to bullying Joey in order to feel like a real man.

David now lives with his father, who is prone to drinking, and his aunt, Ellen. The latter upbraids the father for not being a good example to his son. David's father says that all he wants is for David to become a real man. Later, David begins drinking, too, and drinks and drives once, ending up in an accident. Back home, the two men talk, and David convinces his father to let him skip college and get a job instead. He then decides to move to France to find himself.

After a year in Paris, penniless, he calls Jacques, an older homosexual acquaintance, to meet him for supper so he can ask for money. (In a prolepsis, Jacques and David meet again and discuss Giovanni's fall.) The two men go to Guillaume's gay bar. They meet Giovanni, the new bartender, at whom Jacques tries to make a pass until he gets talking with Guillaume. Meanwhile, David and Giovanni become friends. Later, they all go to a restaurant in Les Halles. Jacques enjoins David not to be ashamed to feel love; they eat oysters and drink white wine. Giovanni recounts how he met Guillaume in a cinema, how the two men had dinner together because Giovanni wanted a free meal. He also explains that Guillaume is prone to making trouble. Later, the two men go back to Giovanni's room and they have sex.

Flashing forward again to the day of Giovanni's execution, David is in his house in the South of France. The caretaker comes round for the inventory, as he is moving out the next day. She encourages him to get married, have children, and pray.

Part two[edit]

David moves into Giovanni's small room. They broach the subject of Hella, about whom Giovanni is not worried, but who reveals the Italian's misogynistic prejudices about women and the need for men to dominate them. David then briefly describes Giovanni's room, which is always in the dark because there are no curtains and they need their own privacy. He goes on to read a letter from his father, asking him to go back to America, but he does not want to do that. The young man walks into a sailor; David believes the sailor is a gay man, though it is unclear whether this is true or the sailor is just staring back at David.

A subsequent letter from Hella announces that she is returning in a few days, and David realizes he has to part with Giovanni soon. Setting off to prove to himself that he is not gay, David searches for a woman with whom he can have sex. He meets a slight acquaintance, Sue, in a bar and they go back to her place and have sex; he does not want to see her again and has only just had her to feel better about himself. When he returns to the room, David finds a hysterical Giovanni, who has been fired from Guillaume's bar.

Hella eventually comes back and David leaves Giovanni's room with no notice for three days. He sends a letter to his father asking for money for their marriage. The couple then runs into Jacques and Giovanni in a bookshop, which makes Hella uncomfortable because she does not like Jacques's mannerisms. After walking Hella back to her hotel room, David goes to Giovanni's room to talk; the Italian man is distressed. David thinks that they cannot have a life together and feels that he would be sacrificing his manhood if he stays with Giovanni. He leaves, but runs into Giovanni several times and is upset by the 'fairy' mannerisms that he is developing and his new relationship with Jacques, who is an older and richer man. Sometime later, David runs into Yves and finds out Giovanni is no longer with Jacques and that he might be able to get a job at Guillaume's bar again.

The news of Guillaume's murder suddenly comes out, and Giovanni is castigated in all the newspapers. David fancies that Giovanni went back into the bar to ask for a job, going so far as to sacrifice his dignity and agree to sleep with Guillaume. He imagines that after Giovanni has compromised himself, Guillaume makes excuses for why he cannot rehire him as a bartender; in reality, they both know that Giovanni is no longer of interest to Guillaume's bar's clientele since so much of his life has been played out in public. Giovanni responds by killing Guillaume in rage. Giovanni attempts to hide, but he is discovered by the police and sentenced to death for murder. Hella and David then move to the South of France, where they discuss gender roles and Hella expresses her desire to live under a man as a woman. David, wracked with guilt over Giovanni's impending execution, leaves her and goes to Nice for a few days, where he spends his time with a sailor. Hella finds him and discovers his bisexuality, which she says she suspected all along. She bitterly decides to go back to America. The book ends with David's mental pictures of Giovanni's execution and his own guilt.

Characters[edit]

- David, a blond American and the protagonist. His mother died when he was five years old.

- Hella, David's girlfriend. They met in a bar in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. She is from Minneapolis and moved to Paris to study painting, until she threw in the towel and met David by serendipity. Throughout the novel David intends to marry her.

- Giovanni, a young Italian man who left his village after his girlfriend gave birth to a dead child. He works as a waiter in Guillaume's gay bar. Giovanni is the titular character whose romantic relationship with David leads them to spend a large amount of the story in his apartment. Giovanni's room itself is very dirty with rotten potatoes and wine spilled across the place.

- Jacques, an old American businessman, born in Belgium.

- Guillaume, the owner of a gay bar in Paris.

- The Flaming Princess, an older man who tells David inside the gay bar that Giovanni is very dangerous.

- Madame Clothilde, the owner of the restaurant in Les Halles.

- Pierre, a young man at the restaurant.

- Yves, a tall, pockmarked young man playing the pinball machine in the restaurant.

- The Caretaker in the South of France. She was born in Italy and moved to France as a child. Her husband's name is Mario; they lost all their money in the Second World War, and two of their three sons died. Their living son has a son, also named Mario.

- Sue, a blonde girl from Philadelphia who comes from a rich family and with whom David has a brief and regretful sexual encounter.

- David's father. His relationship with David is masked by artificial heartiness; he cannot bear to acknowledge that they are not close and he might have failed in raising his son. He married for the second time after David was grown but before the action in the novel takes place. Throughout the novel David's father sends David money to sustain himself in Paris and begs David to return to America.

- Ellen, David's paternal aunt. She would read books and knit; at parties she would dress skimpily, with too much make-up on. She worried that David's father was an inappropriate influence on David's development.

- Joey, a neighbor in Coney Island, Brooklyn. David's first same-sex experience was with him.

- Beatrice, a woman David's father sees.

- The Fairy, whom David met in the army, and who was later discharged for being gay.

Major themes[edit]

Social alienation[edit]

One theme of Giovanni's Room is social alienation. Susan Stryker notes that prior to writing Giovanni's Room, James Baldwin had recently emigrated to Europe and 'felt that the effects of racism in the United States would never allow him to be seen simply as a writer, and he feared that being tagged as gay would mean he couldn't be a writer at all.'[1] In Giovanni's Room, David is faced with the same type of decision; on the surface he faces a choice between his American fiancée (and value set) and his European boyfriend, but ultimately, like Baldwin, he must grapple with 'being alienated by the culture that produced him.'[1]

Identity[edit]

In keeping with the theme of social alienation, this novel also explores the topics of origin and identity. As English Professor Valerie Rohy of the University of Vermont argues, 'Questions of origin and identity are central to James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, a text which not only participates in the tradition of the American expatriate novel exemplified by Stein and, especially, by Henry James but which does so in relation to the African-American idiom of passing and the genre of the passing novel. As such, Giovanni’s Room poses questions of nationalism, nostalgia, and the constitution of racial and sexual subjects in terms that are especially resonant for contemporary identity politics.[3]

Masculinity[edit]

David grapples with insecurities pertaining to his masculinity throughout the novel. He spends much of his time comparing himself to every man he meets, ensuring that his performative masculinity allows him to 'pass' while negotiating the public sphere. For David, masculinity is intertwined with sexual identity, and thus he believes that his same-sex desires act against his masculinity. Baldwin seems to direct the source of his toxic masculinity towards David's father, as he takes on many of his father's problematic traits. David craves an authority figure and blames his father's lack of authority and responsibility for many of his struggles throughout the novel. This comes to a head when David drunk-drives (a habit he assigns to his father) and is involved in an accident. When his father arrives all he can say is: 'I haven't done anything wrong have I?'.[4] This ends his relationship with his father and cements his toxic masculine behaviours.

Manhood[edit]

The phrase 'manhood' repeats throughout the book, in much the same ways that we find masculinity manifesting itself. The difference between the two themes, in this case, is that David's manhood seems to be more to do with his sexual relationships, whereas his masculinity is guided by learned public behaviours he claims to inherit from his father. The self-loathing and projecting that ensues seems to depict the final blow to a man who already had a great amount of dysphoria. Baldwin's positioning of manhood within the narrative align it also with nationhood, sexuality and all facets of performance within the public sphere. Josep Armengol linked Baldwin's description of manhood as a way of him navigating his experiences of blackness in the LGBTQ+ community, particularly when David describes his earliest same-sex encounter with a boy called Joey. In this description 'black' becomes a motif for experience and his dark thoughts surrounding Joey and his body.[5]

LGBTQ+ spaces and movement in the public sphere[edit]

Much of the integral plot of Giovanni's Room occurs within queer spaces, with the gay bar David frequents being the catalyst that not only drives the plot, but allows it to occur. The bar acts as a mediator for David, Baldwin uses this setting to bring up much of the conflict of the novel, however, it remains a place that David returns to. Baldwin's novel is one of the most accurate portrayals of LGBTQ+ people navigating the public and private sphere of its time.[citation needed] It negotiates the behaviour of publicly LGBTQ+ people alongside those who are still 'closeted', like David, and how these differing perspectives have an effect on the individual as well as the community that they navigate.

Homosexuality/Bisexuality[edit]

Giovanni 27s Rooms

Sexuality is the singular, major theme of Baldwin's novel. However, he layers this reading of sexuality by making David's internal conflict not only between homosexuality and heteronormativity but also, between homosexuality and bisexuality.[citation needed] This layered experience reinforces the notion that David's experience of sexuality are tied to his experience of gender norms.[citation needed] He struggles with the idea that he can be attracted to people of either gender because he sees it as proof of his fragile masculinity. In creating this manifestation, Baldwin fairly accurately describes the male bisexual experience of the time, the feeling of indecisiveness and insecurity. It is this portrayal of bisexuality and the experience of bi-erasure that make Baldwin's novel particularly unique.[citation needed]

Question of bisexuality[edit]

Ian Young argues that the novel portrays homosexual and bisexual life in western society as uncomfortable and uncertain, respectively. Young also points out that despite the novel's 'tenderness and positive qualities' it still ends with a murder.[6]

Recent scholarship has focused on the more precise designation of bisexuality within the novel. Several scholars have claimed that the characters can be more accurately seen as bisexual, namely David and Giovanni. As Maiken Solli claims, though most people read the characters as gay/homosexual, '. . . a bisexual perspective could be just as valuable and enlightening in understanding the book, as well as exposing the bisexual experience.'[7]

Though the novel is considered a homosexual and bisexual novel, Baldwin has on occasion stated that it was 'not so much about homosexuality, it is what happens if you are so afraid that you finally cannot love anybody'.[8] The novel's protagonist, David, seems incapable of deciding between Hella and Giovanni and expresses both hatred and love for the two, though he often questions if his feelings are authentic or superficial.

Inspiration[edit]

An argument can be made that David resembles Baldwin in Paris as he left America after being exposed to excessive racism. David, though not a victim of racism like Baldwin himself, is an American who escapes to Paris. However, when asked if the book was autobiographical in an interview in 1980, Baldwin explains he was influenced by his observations in Paris, but the novel wasn't necessarily shaped by his own experiences:

'No, it is more of a study of how it might have been or how I feel it might have been. I mean, for example, some of the people I have met. We all met in a bar, there was a blond French guy sitting at a table, he bought us drinks. And, two or three days later, I saw his face in the headlines of a Paris paper. He had been arrested and was later guillotined. That stuck in my mind.'[8]

Literary significance and criticism[edit]

Even though Baldwin states that 'the sexual question and the racial question have always been entwined', in Giovanni's Room, all of the characters are white.[5] This was a surprise for his readers, since Baldwin was primarily known by his novel Go Tell It On The Mountain, which puts emphasis on the African-American experience.[9] Highlighting the impossibility of tackling two major issues at once in America, Baldwin stated:[9]

I certainly could not possibly have—not at that point in my life—handled the other great weight, the ‘Negro problem.’ The sexual-moral light was a hard thing to deal with. I could not handle both propositions in the same book. There was no room for it.

Nathan A. Scott Jr., for example, stated that Go Tell It On the Mountain showed Baldwin's 'passionate identification' with his people whereas Giovanni's Room could be considered 'as a deflection, as a kind of detour.'[10] Baldwin's identity as a gay and black man was questioned by both black and white people. His masculinity was called into question, due to his apparent homosexual desire for white men - this caused him to be labelled as similar to a white woman. He was considered to be 'not black enough' by his fellow race because of this, and labeled subversive by the Civil Rights Movement leaders.[5]

Baldwin's American publisher, Knopf, suggested that he 'burn' the book because the theme of homosexuality would alienate him from his readership among black people.[11] He was told, 'You cannot afford to alienate that audience. This new book will ruin your career, because you’re not writing about the same things and in the same manner as you were before, and we won’t publish this book as a favor to you.'[9] However, upon publication critics tended not to be so harsh thanks to Baldwin's standing as a writer.[12]Giovanni's Room was ranked number 2 on a list of the best 100 gay and lesbian novels compiled by The Publishing Triangle in 1999.[13]

On November 5, 2019, the BBC News listed Giovanni's Room on its list of the 100 most influential novels.[14]

The 2020 novel Swimming in the Dark by Polish writer Tomasz Jedrowski presents a fictionalized depiction of LGBTQ life in the Polish People's Republic.[15] Citing Giovanni's Room as a major influence in his writing, Jedrowski pays homage to Baldwin by incorporating the novel into his narrative, the two main characters beginning an affair after one lends a copy of Giovanni's Room to the other.[16]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ abcStryker, Susan. Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2001), p. 104.

- ^Bronski, Michael, ed. Pulp Friction: Uncovering the Golden Age of Gay Male Pulps. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2003, pp. 10–11.

- ^Rohy, Valerie, 'Displacing Desire: Passing, Nostalgia, and Giovanni’s Room.' In Elaine K. Ginsberg (ed.), Passing and the Fictions of Identity, Durham: Duke University Press, 1996, pp. 218–32.

- ^Baldwin, James. Giovanni's room. Dell. p. 26. ISBN0345806565.

- ^ abcArmengol, Josep M. (March 2012). 'In the Dark Room: Homosexuality and/as Blackness in James Baldwin's'. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 37 (3): 671–693. doi:10.1086/662699. S2CID144040084.

- ^Young, Ian, The Male Homosexual in Literature: A Bibliography, Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1975, p. 155.

- ^Solli, Maiken, 'Reading Bisexually: Acknowledging a Bisexual Perspective in Giovanni's Room, The Color Purple and Brokeback Mountain. MA thesis. University of Oslo, 2012.

- ^ abBaldwin, James, and Fred L. Standley. Conversations with James Baldwin, University of Mississippi, 1996, p. 205.

- ^ abcTóibín, Colm. 'The Unsparing Confessions of 'Giovanni’s Room', New Yorker. February 26, 2016.

- ^Scott, Nathan A., Jr. 1967. 'Judgment Marked by a Cellar: The American Negro Writer and the Dialectic of Despair', Denver Quarterly 2(2):5–35.

- ^Eckman, Fern Marja, The Furious Passage of James Baldwin, New York: M. Evans & Co., 1966, p. 137.

- ^Levin, James, The Gay Novel in America, New York:Garland Publishing, 1991, p. 143.

- ^The Publishing Triangle's list of the 100 best lesbian and gay novels

- ^'100 'most inspiring' novels revealed by BBC Arts'. BBC News. 2019-11-05. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

The reveal kickstarts the BBC's year-long celebration of literature.

- ^Shapiro, Ari. 'Tomasz Jedrowski's Debut Novel Tells Teenage Love Story In '80s Poland'. NPR.org. National Public Radio, Inc. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^Bollen, Christopher (21 February 2020). 'The Author Tomasz Jedrowski Keeps Coming Back to Giovanni's Room'. Interview Magazine. Crystal Ball Media. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

References[edit]

- Austen, Roger (1977). Playing the Game: The Homosexual Novel in America (1st ed.). Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company. ISBN978-0-672-52287-1.

- Bronski, Michael (2003). Pulp Friction: Uncovering the Golden Age of Gay Male Pulps (1st ed.). New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN978-0-312-25267-0.

- Eckman, Fern Marja (1966). The Furious Passage of James Baldwin (1st ed.). New York: M. Evans & Co.

- Levin, James (1991). The Gay Novel in America (1st ed.). New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN978-0-8240-6148-7.

- Sarotte, Georges-Michel (1978). Like a Brother, Like a Lover: Male Homosexuality in the American Novel and Theatre from Herman Melville to James Baldwin (1st English ed.). New York: Doubleday. ISBN978-0-385-12765-3.

- Stryker, Susan (2001). Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback (1st ed.). San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN978-0-8118-3020-1.

- Young, Ian (1975). The Male Homosexual in Literature: A Bibliography (1st ed.). Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN978-0-8108-0861-4.

Michael Raeburn was in his early 30s when he first met James Baldwin in 1974, a chance encounter at the London book launch for If Beale Street Could Talk. Raeburn was an aspiring filmmaker and screenwriter, with just one short film on his resume, while Baldwin was a literary giant, an essayist, and a civil rights activist. The connection between the two was instantaneous. “He was an extremely influential figure in my life,” Raeburn says. “We were very strangely connected in an almost psychic way. I knew when he would arrive somewhere—he’d travel to New York City, and I would be aware of when he’d arrive at his house.”

The decade was a transformative one in Baldwin’s life. Joyce Carol Oates penned a favorable review of Beale Street for the New York Times, writing the work of fiction was “timeless” and “ultimately optimistic”:

Baldwin constantly understates the horror of his characters’ situation in order to present them as human beings whom disaster has struck, rather than as blacks who have, typically, been victimized by whites and are therefore likely subjects for a novel…As society disintegrates in a collective sense, smaller human unity will become more and more important.

And yet, Beale Street was his first novel in nearly six years, and according to Raeburn, Baldwin felt trapped. “He didn’t want to be classified as a black writer or a homosexual writer. He was just a writer,” Raeburn explains. Baldwin was also lonely; he split much of his time living either in Paris or the south of France (along with Turkey) to distance himself and the particular brand of American racism and prejudice (as well as the demands for constant activism: he liked France because he “could think and…he wouldn’t be hassled to go on marches,” claims Raeburn). That separation also created a personal rift. As Raeburn told James Campbell, who wrote Talking at the Gates: The Life of James Baldwin, “There were plenty of people who could entertain him, or who he found attractive one way or another, but not many that he could talk to about books, or about a play, or about his current work.”

Baldwin’s bond to Raeburn, though, was his tether. The budding director was in the midst of writing a book about the political struggles and guerrilla movements in countries like Zimbabwe and South Africa (titled Black Fire, it was ultimately published in 1978), and Raeburn’s literary background appealed to Baldwin. “We spoke endlessly about books,” he says, noting that he also shared Baldwin’s admiration of Marcel Proust, whose language Baldwin “found fascinating.” The two also connected on a more personal level, and what began as that chance encounter transformed into an on-and-off again relationship that lasted until Baldwin’s death in 1987. “I never experienced a relationship in terms of like the one with Jimmy,” says Raeburn. “He himself was staggered by all of it. There was a lot of Giovanni’s Room reflected in our relationship.”

The novel, which was published in 1956, is Baldwin’s gift to the French, as it was his only work ever set entirely in France: told in flashbacks, David, an American, meets Giovanni in Paris and falls in love with the Italian man, who works at a bar owned by Guillaume. Eventually, having been fired and unable to get his job back, Giovanni murders Giuillaume; Giovanni is sentenced to be executed. Meanwhile, in the novel’s present, David is engaged to marry a woman named Hella, but when she finds him in bed with another man, she confesses that she always knew David was gay; she returns to America, leaving David behind in the south of France. The novel’s examination of homosexuality, social alienation, and identity were extremely rare at the time, as was its core theme of questioning American exceptionalism, and the work closely aligned with how Baldwin felt at the time of the novel’s publication. (It also was criticized for the whiteness of its characters, a critique which Baldwin acknowledged to be indeed troublesome but unavoidable—”I certainly could not possibly have—not at that point in my life—handled the other great weight, the ‘Negro problem.’ The sexual-moral light was a hard thing to deal with. I could not handle both propositions in the same book. There was no room for it,’’ he once said.)

Which is why Baldwin approached Raeburn to adapt his most beloved novel into a screenplay in 1978. “There are other ways we can love each other, why don’t you do a screenplay of Giovanni’s Room?,” Raeburn recalls. And thus began a project to develop the novel into a film, an endeavor that stretched over several years and would have possibly included an all-star cast of Robert De Niro (who was then interested in playing what an associate described as a “positive gay character“) and Marlon Brando (as Guillaume, owner of the Parisian gay bar). It would have been the first ever adaptation of one of Baldwin’s works—he had previously sought to adapt Another County (1962) and Blues for Mr. Charlie (1964), but both films never progressed, and it wasn’t until PBS adapted Go Tell It On the Mountain in 1984 that a Baldwin-penned novel was produced for either television or film (Barry Jenkins’ If Beale Street Could Talk, which debuts in late November and has already garnered massive Oscar buzz, is the second).

Baldwin always believed his works would translate well to other mediums, so it’s strange that there have been so few attempts to adapt his writings since his death. And even though Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, the highly-acclaimed 2016 documentary, jump-started interest again in Baldwin—”After Jimmy passed, books started to disappear from shelves, but that doc was a sudden blast,” says Raeburn—James Baldwin’s estate appears to be moving slowly. According to Eileen Ahearn, the former assistant to Toni Morrison who currently oversees the estate, there will not be a rush of Baldwin-related material unleashed in the near future: “We have always been very cautious about movie rights, and especially with Beale Street about to come out, it is a very sensitive topic, and one I don’t want to discuss with a journalist.”

Though before Ahearn hung up, she did clarify that the moratorium also extended to any adaptations of Giovanni’s Room. “I get calls constantly about Giovanni’s Room, and I have for years, but [the estate] isn’t going to do anything at the moment,” she says. Which means that even though Raeburn has sat on a script for the past forty years, a script he co-wrote with Baldwin and one that features new characters and dialogue, and is one of the final remaining works of Baldwin’s legacy, he is still in a holding pattern. “Eileen told me to cool it at the moment,” he says, which is a difficult proposition for someone in his mid-70s. “The estate wants to see what happens with Beale Street,” he further explains. “They could sell everything Jimmy has written tomorrow, and then it would be a deluge [of films], and they believe it would be a disaster.”

He adds, “They are also rather nervous now about Giovanni’s Room, for reasons which I am not quite clear—it’s a story about race that isn’t disguised as a class story.” So Raeburn’s screenplay, which is housed in his London flat, currently lays dormant. “Jimmy wanted to make the film,” he says. “We did it out of the sincere commitment and belief that a good film would be made of this script.”

The collaborators began to meet around 1978—collaborating either in Paris or in Saint Paul de Vence, in southeastern France—to discuss how to transform a book told largely in flashbacks into a seamless script that wouldn’t confuse the audience: Raeburn sketched the narrative flow while Baldwin crafted the dialogue. “Jimmy is a novelist, not a screenwriter, so it would get a bit wordy,” explains Raeburn. “But his dialogue was always brilliant.”

More than 20 years after he first published the novel, Baldwin felt it time to address the text’s lack of diversity, which he sought to reflect in the screenplay. The new characters—friends of Giovanni at the bar—would both add complementary voices while also potentially silencing those critics who harped about the novel’s overall whiteness. This initial foray into adapting the novel would hopefully provide a roadmap of how to get past the book’s opening, which features Giovanni’s impending execution. “We were grappling with structure. We wanted to get to the end of a very rough draft because then we could start again,” says Raeburn. “Jimmy understood that, but he would still keep saying, ‘There is too much of this thing at the beginning,’ to which I’d respond, ‘We’ll deal with it, but let’s get to the end first!'”

Raeburn recalls that the first draft abruptly ended on page 80, about three-quarters through the novel, with Baldwin adding to the script:

David says ‘merci beaucoup’. David picks up his glass and toasts the surprised waiter…[and] he starts tapping out a song which he also hums.

At which point, Raeburn wrote, “To be continued!!” It never was. “I couldn’t get anyone interested in the project,” he says. “People weren’t willing to watch a homosexual love story back then. They couldn’t get their heads around it.” Though the work didn’t necessarily stop—Baldwin met with Marlon Brando around 1979 to discuss the actor possibly playing Guillaume. “With Marlon on board, anything was possible,” says Raeburn. The three met at a private hotel on the left bank in the Quartier Latin where Brando was staying, and bypassed the paparazzi by sneaking out of the compound in an unmarked taxi. The group drove around Paris for two hours discussing Giovanni’s Room; by the end of the ride, Raeburn says Brando had signed on to the project.

The impact was instantaneous. Baldwin and Raeburn sketched out a second, 211-page draft of “clean, presentable text” which they intended to present to Brando and possibly De Niro—at the Deauville Film Festival (attended by both Baldwin and Raeburn), a purported friend of the actor’s mentioned he was interested in roles outside of his comfort zone. But before they could build any further momentum—”We had finally figured out the direction we wanted to take”—Raeburn learned of an unexpected complication: Jay Acton, Baldwin’s literary agent, demanded $100,000 for the book’s option.

“Jimmy was furious—he felt like he was a prisoner of his agent,” Raeburn says. “We could go on writing quite happily, but never get anywhere unless came up with $100,000.” Neither Raeburn nor Baldwin had access to that sort of financing, which meant no De Niro or Brandon—there could be no official contracts without first securing the option. And so Raeburn shelved the script. The plan was to take it up again when the time was right, but when Baldwin died in 1987, it had been six years since the two met to discuss Giovanni’s Room.

“The whole thing is still a work in progress,” Raeburn says.

But the renewed interest in Baldwin’s works, coalescing around If Beale Street Could Talk, has reinvigorated Raeburn’s efforts to finally complete the screenplay—the only draft in existence with original dialogue from Baldwin—and actually make the film. Raeburn says he has spoken with Ahearn, who advised him to “start over from zero,” but the director hopes to make make a more personal pitch: allow him to option the book for a year. “It’s so much more possible to make this film today,” he says. “Jimmy didn’t want to make a studio film. He wanted to make a film that has a French feel with subtitles.”

Giovanni 27s Roomba

He continues, “Jimmy would be delighted, and they owe it to him.”